Contraception

Any method, medicine, or device used to prevent pregnancyCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

In this section:

- Introduction

- Priority Questions

- Unique Concerns

- Contraception Counseling

- Myths and Facts

- CF-Specific Considerations

- Hormonal Contraception

- Other Reasons to take Contraception

- Post-Transplant

- CFTR Modulators

- Psychosocial

- Further Research

- Peer-to-Peer Advice

- Resource Links

- Works Cited

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

The decision to become pregnant carries special considerations for women with CF, mainly because pregnancy can involve some high-risk scenarios for these women [see Pregnancy and Family Building chapters]. It is, therefore, essential for women with CF who are sexually active but not actively trying to become pregnant to consider using contraception. Women need to decide which contraceptive method is best for them. The choice is each individual’s alone to make. Still, discussions with a woman’s health provider, CF provider, and, where relevant, the patient’s partner can help inform a woman about CF’s decisions.

- Do you want to get pregnant within the next year?

- During the next 5 years?

- What form of contraception are you using, if any?

- Do you have your partner use condoms to prevent pregnancy and STIs?

- How do you feel about your current form of contraception?

- Are you in a monogamous relationship?

*Providers should be able to discuss all available contraceptive options with the patient if she/they want(s) to start or change their contraceptive method.

- What risks and benefits does each contraceptive method have for a woman with CF?

- Are there any potential pharmaceutical interactions between my CF medications and my form of birth control? If so, what are they?

- Are there any heightened risks to using that are greater in a CF patient than in the general population?

- Are there any recommendations for a particular type of birth control for my specific medical concerns?

- If I am interested in a contraceptive implant, what are my pain control options for placement?

*These questions can also be asked to a pharmacist specializing in complex care.

Contraception in CF

Multiple studies suggest that females with CF can now expect to face the same sexual and reproductive health milestones as non-CF US females, including age of onset of sexual activity, number of partners, and sexual activity rate.[1–4] These studies also suggest that rates of contraception use among females with CF are lower than that of the non-CF US female population.[1–4] Meiss and Kazmerski report, for instance, a 15% lower use of contraception in non-CF females.[3,5] Women with CF commonly use condoms and oral hormonal contraceptive pills as forms of contraception, which corresponds with the same preferences for the general US female population.[6–9] Like others, females with CF have increased their use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), like IUDs and implants, from 8% in 2016 to 27% in 2020.[4,7–9] Two reasons for this increase could be: 1) the interaction of Orkambi™ with hormonal contraception and

2) the large number of females with CF who participate in clinical trials that require contraception use and involve counseling by the research team.[10]

*Male and female condoms protect against STIs.

**To learn more about different forms of birth control, please see the Resource Section at the end of this chapter.

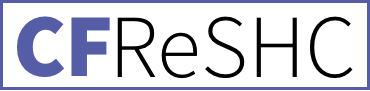

What to know about birth control and modulators

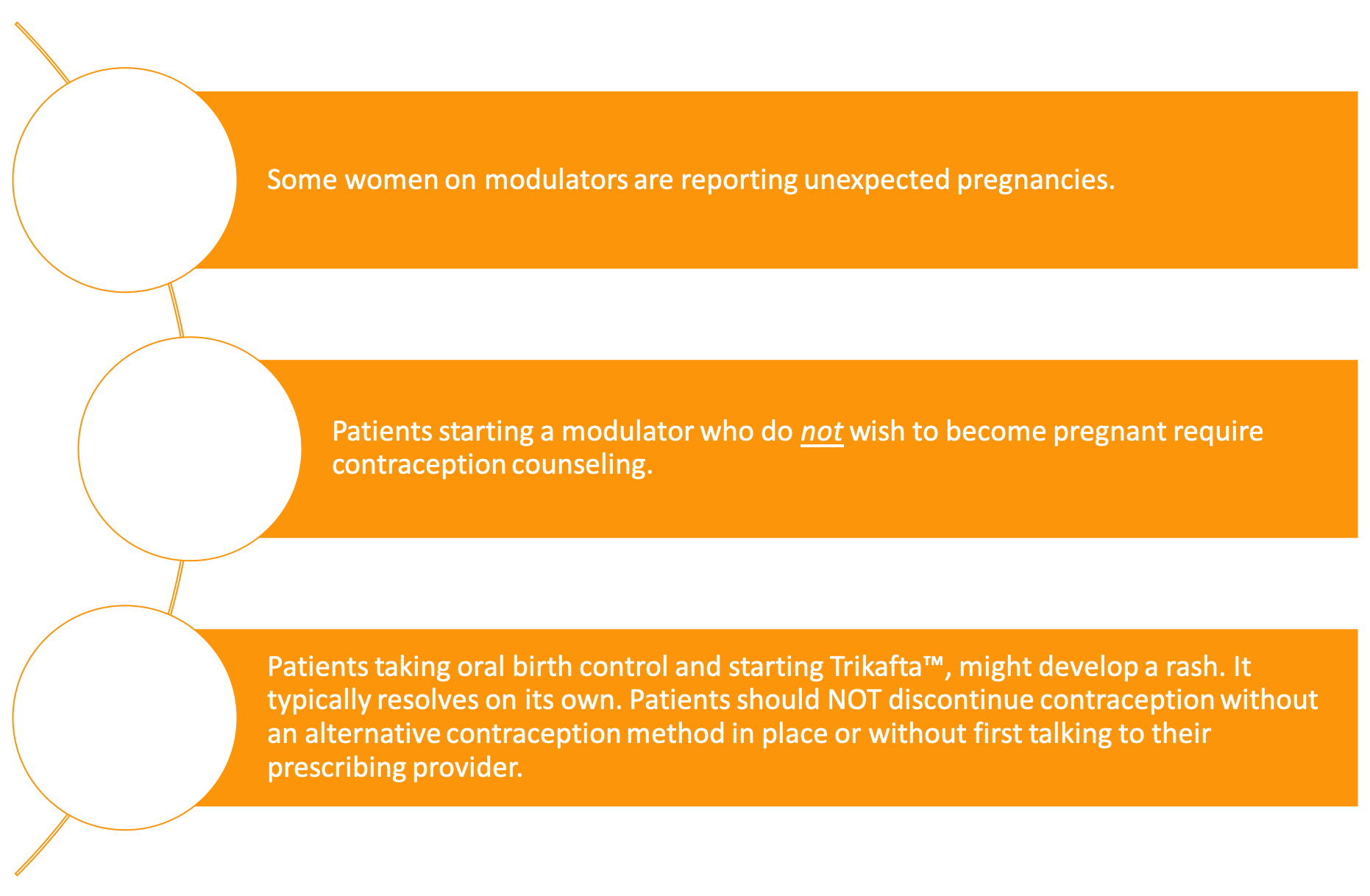

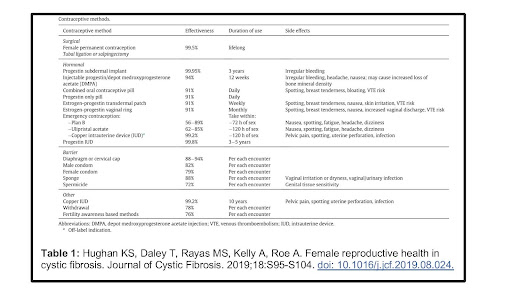

What kinds of contraception exist?

*For their part, male and female condoms can protect against STIs.

**To learn more about forms of birth control, please see the Resource Section at the end of this chapter.

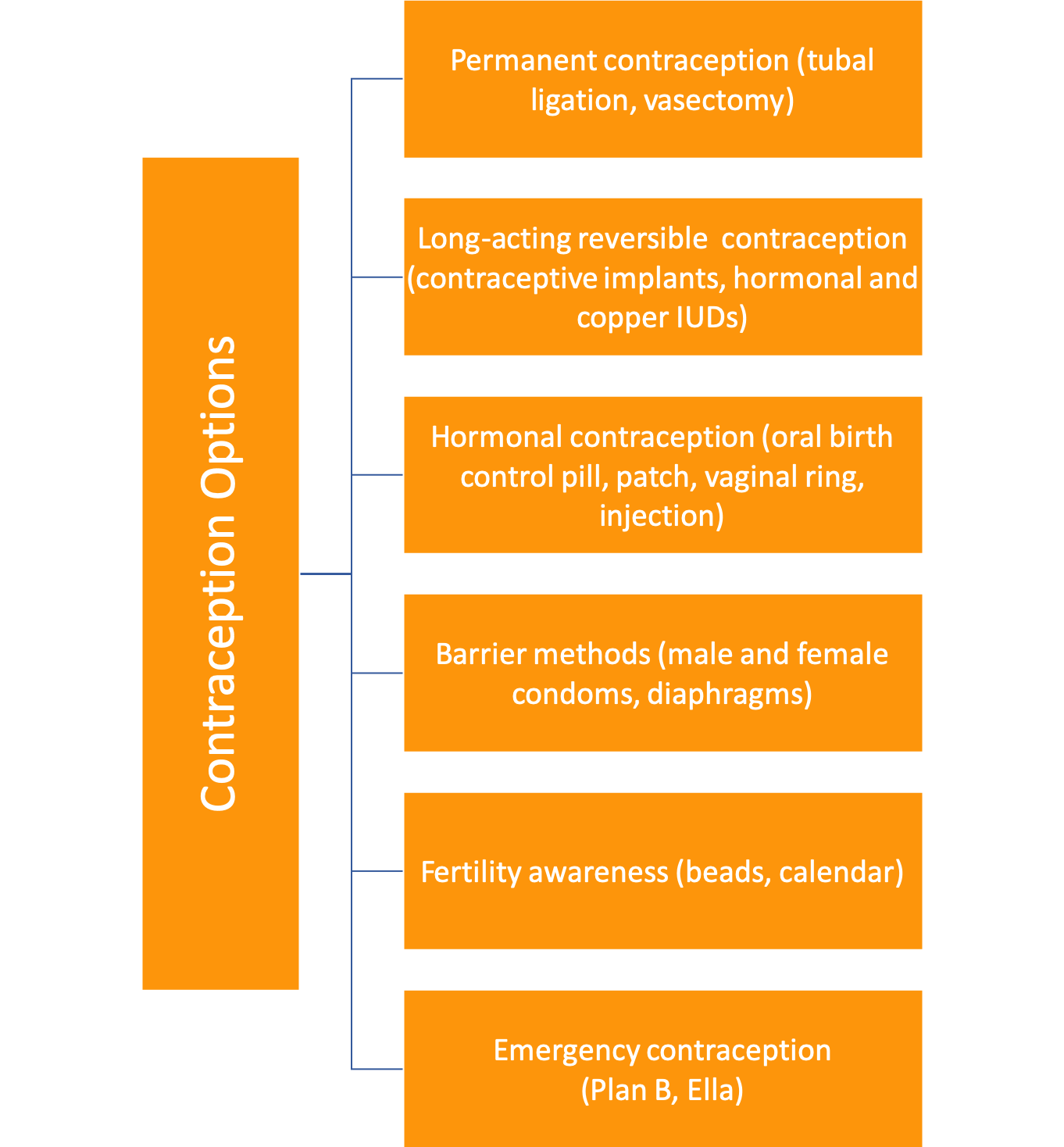

Contraception Counseling

Females with CF receive their contraceptive care from a variety of providers. In a survey of women with CF published in 2018, Kazmerski et al. found that OB/GYNs prescribe or administer 66% of contraceptives to women with CF, while CF clinics prescribe 7%.[11] Primary care providers (PCPs) and others prescribe only a tiny percentage.[11] Women with CF typically view their CF doctor as their primary physician, and 41% report no other primary care provider.[4,11] Researchers have shown that contraception counseling directly impacts contraception use, yet only 9% of young adults with CF have ever received such counseling from any source.[5] Women with CF make contraceptive choices within the context of their CF and generally prefer to receive reproductive counseling from their CF team due to a perception of inadequate CF-specific knowledge among women’s health providers.[11] A study conducted in France (2019) found that introducing a gynecological consult into the CF clinic increased rates of contraceptive use – especially of LARCs– among women with CF.[12] Even though American CF clinicians believe contraception counseling is an integral part of CF care, only a minority counsel their patients.[13] Barriers to patients and providers talking about contraception include patient and provider discomfort, lack of time, and lack of training in contraception counseling.[13] Women with CF report feeling that they had been inadequately educated on how different contraceptive methods would interact with their CF and medications and that there was a significant disconnect between their OB/GYNs and their CF teams.[5,11] Women with CF desire coordinated, defragmented reproductive health care and disease-specific reproductive health discussions.[11] Ideally, providers should give contraception counseling to patients on all medically eligible contraception options to allow them to make the appropriate choices for their lives. The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (US-MEC) provides “recommendations for using specific contraceptive methods by women…who have certain…medical conditions.” CF was added to this chart in 2016 through the work of Dr. Emily Godfrey.[14] While safety data is currently limited for CF, the US-MEC table indicates “no risk” for most forms of contraception for CF (level 1). Only combined hormonal contraceptives are rated a Level 2, denoting that the “advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks.”[14] Neither level confers a contraindication to using a method; patient preference can determine the method used.[6] It is important to note that many people with CF have comorbidities such as transplant status, liver disease, and diabetes that are also listed separately in the US-MEC guidelines. Please consult those specific guidelines and discuss which contraception options are safe and effective for each patient.

Myths about Contraception

Women with CF hold many misconceptions about contraceptive methods, which can reduce overall use.[15] LARCs are the most effective at preventing pregnancy of all methods, and females with CF typically experience minimal side effects.[6] The following modules clarify common myths about fertility and contraception.[6,7,14,16–19]

Women with CF are infertile.

False

Women with CF are not infertile. However, 35% experience subfertility, meaning it may take longer than one year to become pregnant, or medical assistance may be needed to conceive. Highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) likely improves fertility, so rates of subfertility are expected to decline as the use of HEMT grows. Sexually active women with CF are advised to use contraception unless they are actively trying to become pregnant.

[see the (In)Fertility chapter]

Antibiotics make hormonal birth control less effective.

Mostly False

Most antibiotics that females with CF use do not routinely interfere with hormonal birth control; however, rifamycins, a family of antibiotics, do [see the Hormonal Contraception section below for more information]. Some antifungals may also interfere. When in doubt, consult your doctor or pharmacist.

You cannot take hormonal birth control with modulators.

Partly True

Orkambi™ reduces the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives (e.g., oral contraceptives, patch, and ring) in preventing pregnancy, so another form of birth control, like IUDs or barrier methods, should be used for birth control. All other modulators do not reduce the efficacy of hormonal contraceptives.

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs) are hormonal birth control.

Party True

Hormonal IUDs do not contain estrogen but do contain the progestin levonorgestrel. However, only a tiny amount of levonorgestrel enters a female’s bloodstream. Typical CF medications do not make hormonal IUDs less effective at pregnancy prevention. The copper IUD does not contain hormones.

Hormonal contraception is not safe to use if you have diabetes.

False

Combined hormonal contraception is safe to use in patients with diabetes. Studies have not found an increase in blood sugar glucose or insulin production in diabetic patients, except in cases of severe complications. The US-Medical Eligibility Criteria lists hormone-containing birth control as level 2 risk.

IUDs are not safe to use by women with CFRD.

False

All IUDs are safe for women who have CFRD, despite previous concerns that women who had diabetes would be at higher risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. However, the CDC states that this theoretical risk remains unproven.

Sources for this table include Shteinberg, Curtis, Rodriguez, Vertex, and Curtis in Works Cited.

Hormonal Contraception

Unique Considerations for Women with CF

Although infrequent, estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives may increase the risk of blood clots in some females with CF, especially for those with a history of blood clots.[6] Often, females with CF have a higher incidence of blood clots due to liver issues, vitamin K deficiency, and the use of ports and PICC lines.[20]

The use of combined hormonal contraception (CHC) can also limit treatment options for some CF infections. For example, Rifampin or rifabutin therapy, used to treat Methicillin-resistant staph aureus (MRSA) and Non-Tuberculosis Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC), reduces the effectiveness of hormonal contraception.[21] Providers should counsel patients using Rifampin (a medication within the family of rifamycin antibiotics) to either use a second form of birth control (e.g., condoms) or switch birth control methods to a non-systemic method like an IUD.

CF patients have an increased risk of developing osteopenia and osteoporosis due to decreased bone density ( see Bone Health Chapter for more information: Bone Health in Cystic Fibrosis | CFReSHC). Because of these risks, females with CF should be monitored bi-annually with a DEXA scan. Patients may lose bone density if they receive Depo-ProveraⓇ injections, but their bone density can improve after discontinuing it.[22] In recent studies on non-CF adolescents, using combined hormonal contraception with fewer than 30 mcg of estrogen adversely affected peak bone mass acquisition.[23,24] Transdermal options may be superior to oral estrogens for maintaining bone health, though no CF-specific studies have been conducted.[24]

Reasons to Use Contraception Beyond Pregnancy Prevention

Females with CF may benefit from hormonal contraceptives used to treat an underlying medical condition. Females may have amenorrhea (an absence of menstruation) or irregular periods because of low weight, recurrent lung infections, or illness-related stress.[25] Hormonal contraception can help regulate a female’s period or eliminate it, which may be particularly helpful for females with anemia or low iron. Some females with CF may experience fewer pulmonary exacerbations and a slower rate of lung function decline when they use hormonal contraceptives. They may also need fewer courses of antibiotics.[26,27]

The use of hormonal contraception has been shown to reduce inflammation.[28] Hormonal contraception use in adolescents with CF has no adverse effect on FEV₁and may improve lung function if used for more than three years.[26] [See Hormones chapter].

Contraception Post-Transplant

Transplant patients have unique contraceptive challenges. Post-transplant medications containing mycophenolate, such as CellCeptⓇ, can reduce the effectiveness of hormonal birth control and can cause birth defects in a developing fetus. Because the effects can be severe, the drug insert contains a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) and a black box warning from the FDA. As part of the REMS, the FDA requires patients and providers to sign a consent form before transplant to be treated with this class of drugs.[29] Since transplant medications interact with combined hormonal contraception, it is recommended to use another method of birth control to prevent pregnancy during the period in which the patient is using mycophenolate and at least six weeks after stopping.[30] If a patient wants an IUD, it must be placed before transplant. In the first two years after a transplant, there is a small risk of infection.[31] Generally, the US-MEC recommends a female wait a minimum of 1-3 years post-transplant to consider pregnancy. During this time, her contraceptive choices are crucial for her health and well-being.[29]

CFTR Modulators and Contraception

While OrkambiTM interacts with oral contraceptive pills, no other modulator does!

Orkambi ™ interacts with oral contraceptive pills, but no other modulator does. Many females with CF are getting pregnant after starting Trikafta™, resulting in a “Trikafta baby boom.”[18,31] Heltshe et al.reported that females on KalydecoⓇ also have an increased pregnancy rate.[32] These pregnancies highlight the need for providers to initiate conversations with their female patients about contraception choices and pregnancy plans before prescribing modulator therapy.

Besides increased rates of pregnancy, females on Trikafta™ may also have rashes if on hormonal contraceptives.[33] If a female on Trikafta™ experiences a rash, it is important to select another form of birth control before she/they stop their current contraceptive method to prevent an unplanned pregnancy. Condoms and other barrier methods can be used as a last-minute substitute. In these circumstances, it is best to consult a physician.

Psychosocial Implications

Many females with CF are often confused about whether they need contraception; they are also often uncertain about which option is best for them. From a young age, they face concerns about the possibility of being infertile. Consequently, many incorrectly assume they do not need to use contraception when they become sexually active.[13] However, a recent paper reports that up to 38.9% of pregnancies are unplanned in the CF community.[2] In the current political climate, a female with CF who unintentionally becomes pregnant may be unable to access termination easily.[34] Conversations around contraception are, therefore, critically important for persons with chronic illness.

Another concern many females with CF have is whether they are healthy enough to have a family. [see Family Building chapter]. Providers need to understand that decisions about contraceptive use can be difficult for many patients.

Females with CF may decide – possibly at a young age – that they do not want ever to become pregnant. Providers should support these females in their decisions. They may suggest LARCs over permanent forms of contraception to preserve a female’s choice to make a different decision later in her/their life. The provider can refer the patient to a gynecologist who is comfortable with providing permanent contraception to those who do not wish to have children naturally. Of note, preserving patients’ sex organs can offer benefits to females with CF as they transition into menopause. [See the Menopause chapter].

What Female with CF Want to Know More About

There needs to be more research on contraception in CF; one way to aid contraception research would be to add a question or questions about contraception use to the CF Foundation Patient Registry. Such a query would help provide long-term data about the efficacy, safety, lung health, and prescription interactions for each type of contraception and how it impacts women with CF. Godfrey et al. completed a pilot registry project that showed women with CF are amenable to the CFF tracking such information.[7] Future research on contraception and CF should also focus on the comparative safety, efficacy, and side effects of various types of contraceptive options in a rapidly aging CF population. Examples could be a study of the effects of transdermal vs. oral CHCs on bone health or between low- and high-dose oral CHCs.

Personal Narratives

Peer to Peer Advice

- There are many reasons to use hormonal birth control beyond preventing unplanned pregnancy, like treating painful periods, irregular cycles, heavy menstrual flow, acne, etc.

- Who can you talk to about contraception and CF? Find a healthcare professional with whom you feel most comfortable discussing your concerns.

- Assess and reassess your reproductive and contraceptive needs throughout your life.

- If you have side effects from a method of contraception, try another form. Talk to either your CF or women’s health provider about your options.

- Safe sex is essential! Only condoms prevent sexually transmitted infections.

- Yearly pelvic exams are an excellent opportunity to discuss birth control options with your OB/GYN.

- Self-advocate for open communication between your CF team and women’s health provider.

Resources

For comprehensive contraception choices see:

Contraception Method Chart

For medical safety information about contraception:

- CDC US-MEC safety charts

- CDC Medication summary

- There is even an app! Click here for Android and Apple

For more information about CF sexual and reproductive health:

- Center for Young Women’s Health Guide on Contraception

- MyVoice: CF[35]

Works Cited

- Frayman KB, Chin M, Sawyer SM, Bell SC. Sexual and reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(6):685-695. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000731

- Daccò V, Alicandro G, Trespidi L, Gramegna A, Blasi FA. Unplanned pregnancies following the introduction of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy in women with cystic fibrosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023;308(5):1657-1659. doi:10.1007/s00404-023-07153-y

- Meiss LN, Jain R, Kazmerski TM. Family Planning and Reproductive Health in Cystic Fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2022;43(4):811-820. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2022.06.015

- Roe AH, Traxler S, Schreiber CA. Contraception in women with cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of the literature. Contracept Stoneham. 2016;93(1):3-10. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.007

- Kazmerski TM, Sawicki GS, Miller E, et al. Sexual and reproductive health behaviors and experiences reported by young women with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(1):57-63. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2017.07.017

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(3):1-103. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1

- Godfrey EM, Mody S, Schwartz MR, et al. Contraceptive use among women with cystic fibrosis: A pilot study linking reproductive health questions to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation National Patient Registry. Contracept Stoneham Contracept. 2020;101(6):420-426. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.02.006

- Gatiss S, Mansour D, Doe S, Bourke S. Provision of contraception services and advice for women with cystic fibrosis. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2009;35(3):157-160. doi:10.1783/147118909788708075

- Plant BJ, Goss CH, Tonelli MR, McDonald G, Black RA, Aitken ML. Contraceptive practices in women with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7(5):412-414. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2008.03.001

- Heltshe SL, Taylor-Cousar JL. Let’s talk about sex: Behaviors, experience and health care utilization in young women with CF. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(1):5-6. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2017.11.006

- Leech MM, Stransky OM, Talabi MB, Borrero S, Roe AH, Kazmerski TM. Exploring the reproductive decision support needs and preferences of women with cystic fibrosis. Contracept Stoneham Contracept. 2021;103(1):32-37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.10.004

- Rousset-Jablonski C, Reynaud Q, Perceval M, et al. Improvement in contraceptive coverage and gynecological care of adult women with cystic fibrosis following the implementation of an on-site gynecological consultation. Contracept Stoneham. 2019;101(3):183-188. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.10.014

- Kazmerski M Traci M, MD, Borrero M Sonya, MD, Sawicki M Gregory S, MD, et al. Provider Attitudes and Practices toward Sexual and Reproductive Health Care for Young Women with Cystic Fibrosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(5):546-552. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2017.01.009

- Control C for D. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. 2020(9.10.).

- Traxler SA, Chavez V, Hadjiliadis D, Shea JA, Mollen C, Schreiber CA. Fertility considerations and attitudes about family planning among women with cystic fibrosis. Contracept Stoneham Contracept. 2019;100(3):228-233. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.005

- Rodriguez MI. Which medication can mess with birth control? Bedsider. https://www.bedsider.org/features/294-which-medications-can-messwith-birth-control

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals. OrkambiⓇ [package insert] US Food and Drug Administration website. 2015;2020(1.). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206038Orig1s000lbl

- Taylor-Cousar JL, Shteinberg M, Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Jain R. The Impact of Highly Effective Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Modulators on the Health of Female Subjects With Cystic Fibrosis. Clin Ther. 2023;45(3):278-289. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.01.016

- Shteinberg M, Lulu AB, Downey DG, et al. Failure to conceive in women with CF is associated with pancreatic insufficiency and advancing age. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(4):525-529. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2018.10.009

- Blower K, Seifi A, Michelak J, Keyt H. Incidence of VTE in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis: Are They High Risk? Chest. 2016;150(4):1135A. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1245

- Floto RA, Olivier KN, Saiman L, et al. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus recommendations for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2016;71(Suppl 1):i1-i22. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207360

- Pfizer. Depo Provera [drug insert]. Published online 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/020246s036lbl

- Golden NH. Bones and Birth Control in Adolescent Girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;33(3):249-254. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2020.01.003

- Wu M, Hunt WR, Putman MS, Tangpricha V. Oral ethinyl estradiol treatment in women with cystic fibrosis is associated with lower bone mineral density. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2020;20:100223. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2020.100223

- Hughan KS, Daley T, Rayas MS, Kelly A, Roe A. Female reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2019;18 Suppl 2:S95-S104. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.024

- Perrissin-Fabert M, Stheneur C, Veilleux-Lemieux M, et al. Hormonal Contraception Effects on Pulmonary Function in Adolescents with Cystic Fibrosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. Published online 2020. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2020.07.014

- Chotirmall SH, Smith SG, Gunaratnam C, et al. Effect of Estrogen on Pseudomonas Mucoidy and Exacerbations in Cystic Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1978-1986. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1106126

- Holtrop M, Heltshe S, Shabanova V, et al. A Prospective Study of the Effects of Sex Hormones on Lung Function and Inflammation in Women with Cystic Fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(7):1158-1166. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-1064OC

- FDA. Mycophenolate Risk Evaluation Mediation Strategy. US Food and Drug Administration website. 2015;2020(1.). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/rems/Mycophenolate_2015-11-13_REMS_Full

- Pharmaceuticals M. CellCeptⓇ [package insert] US Food and Drug Administration website. Published online 2018.

- Jain R, Taylor-Cousar J. Fertility, Pregnancy and Lactation Considerations for Women with CF in the CFTR Modulator Era. J Pers Med. 2021;11(5):418. doi:10.3390/jpm11050418

- Heltshe SL, Godfrey EM, Josephy T, Aitken ML, Taylor-Cousar JL. Pregnancy among cystic fibrosis women in the era of CFTR modulators. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(6):687-694. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2017.01.008

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Trikafta Package insert. US Food and Drug Administration website. Boston MA. Published online 2019.

- Powell R. Including Disabled People in the Battle to Protect Abortion Rights: A Call-to-Action. Published online April 22, 2022. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4090764

- Stransky OM, Pam M, Ladores SL, et al. Engaging Stakeholders in the Development of a Reproductive Goals Decision AID for Women with Cystic Fibrosis. J Patient Exp J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221077527. doi:10.1177/23743735221077527

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.